Empowering Indigenous Health: The Indigenous Primary Health Care and Policy Research (IPHCPR) Network

The emphasis on learning directly from Indigenous community members, and delivering collaborative solutions resonates with the ethos that the process itself is the work. In line with this philosophy, the goal was to bridge the gap between Indigenous communities and provide an understanding of how the pandemic has impacted marginalized populations in Alberta.

In collaboration with the Indigenous Primary Health Care & Policy Research Network (IPHCPR), I was brought on to explore models of primary care and the intersection of COVID-19 and Indigenous Communities in Alberta. This project leveraged collaborative research and systems mapping as well as methodologies such as Human-Centered Design (HCD) and co-design.

As the lead design researcher, I prioritized a human-centric approach, fostering meaningful connections within the community it serves.

The IPHCPR Network research project is supported by and housed in the Department of Family Medicine, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary; and supported by CIHR under the leadership of the Institute of Indigenous Peoples’ Health and the Institute of Circulatory and Respiratory Health. In the heart of Alberta, the IPHCPR Network stands as a dynamic force committed to reshaping the narrative of Indigenous health.

Unveiling the Disproportionate Impact

The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic had strained systems worldwide and led to a dramatic loss of human life. Since its onset, COVID-19 has presented a set of unprecedented challenges to health systems, economies, and marginalized and vulnerable populations. Amongst those marginalized populations are the Indigenous communities in Canada. Existing systemic oppression, genocidal laws and policies already place Indigenous communities in a high-risk state, susceptible to vulnerabilities. Thus, Indigenous communities have disproportionately been affected by the pandemic, whether it is through infections, racism, lack of resources, or overcrowding. Our goal throughout the project was to better understand and highlight these disparities, especially within the healthcare sector.

Right: Map of Indigenous Communities in Alberta (Government of Canada)

Understanding Insights and Stories

During the three-month phase, we reached out to healthcare providers from both Indigenous communities. Our goal was to delve into the intricacies of their experiences, conducting interviews and immersing ourselves in their stories. Complementing this, we conducted standard desk research, uncovering insights from a myriad of healthcare-based organizations—both Indigenous and non-Indigenous-led—across Canada. This dual approach not only provided a comprehensive framework for our research but also ensured the collection of essential data crucial to our understanding. As the narratives unfolded, a plethora of barriers, access points, and nuanced patterns emerged, paving the way for an in-depth analysis and synthesis of the gathered data. What became apparent was the distinctiveness in the COVID-19 responses of the two communities being engaged. However there were also striking overlaps and shared stories.

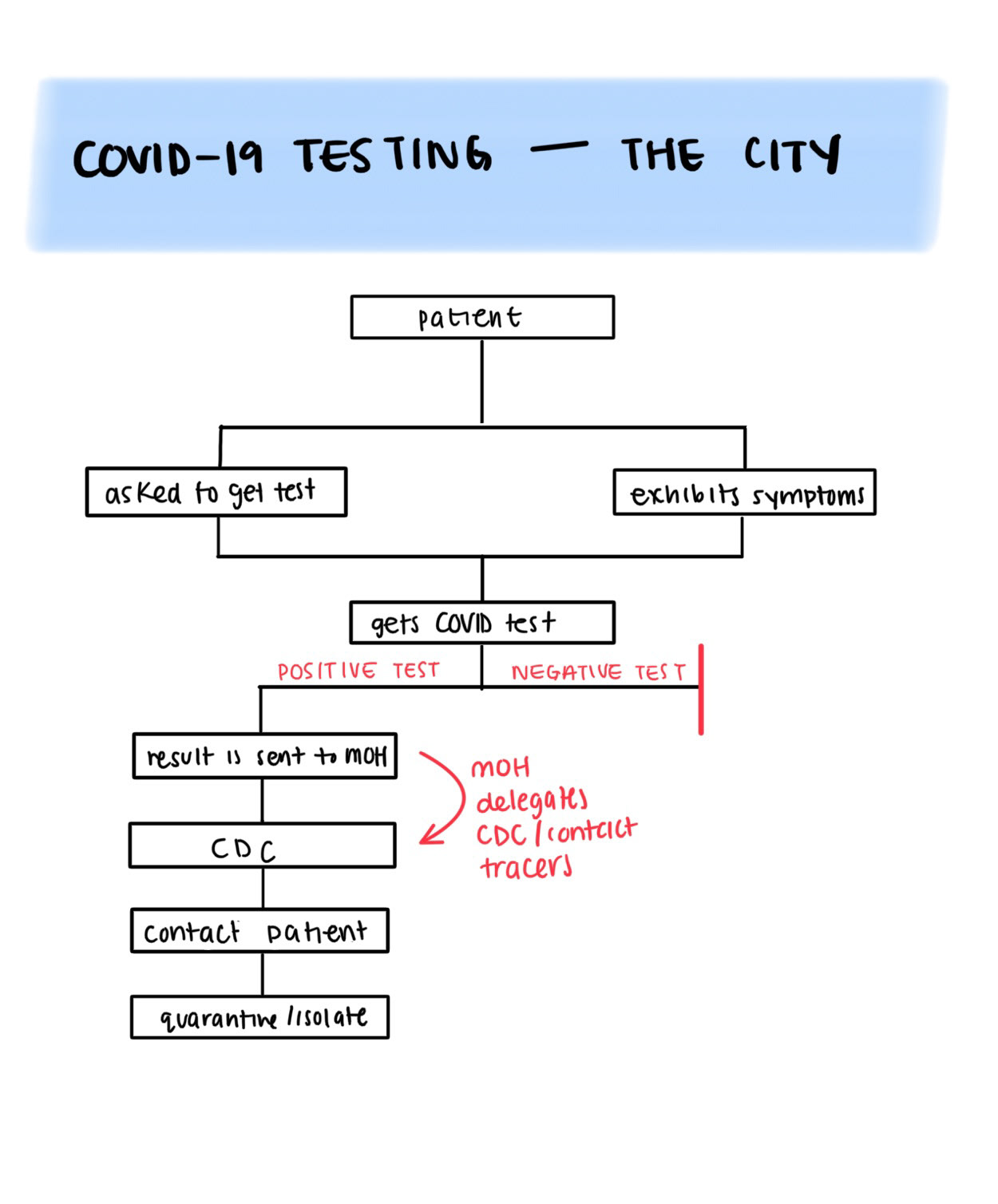

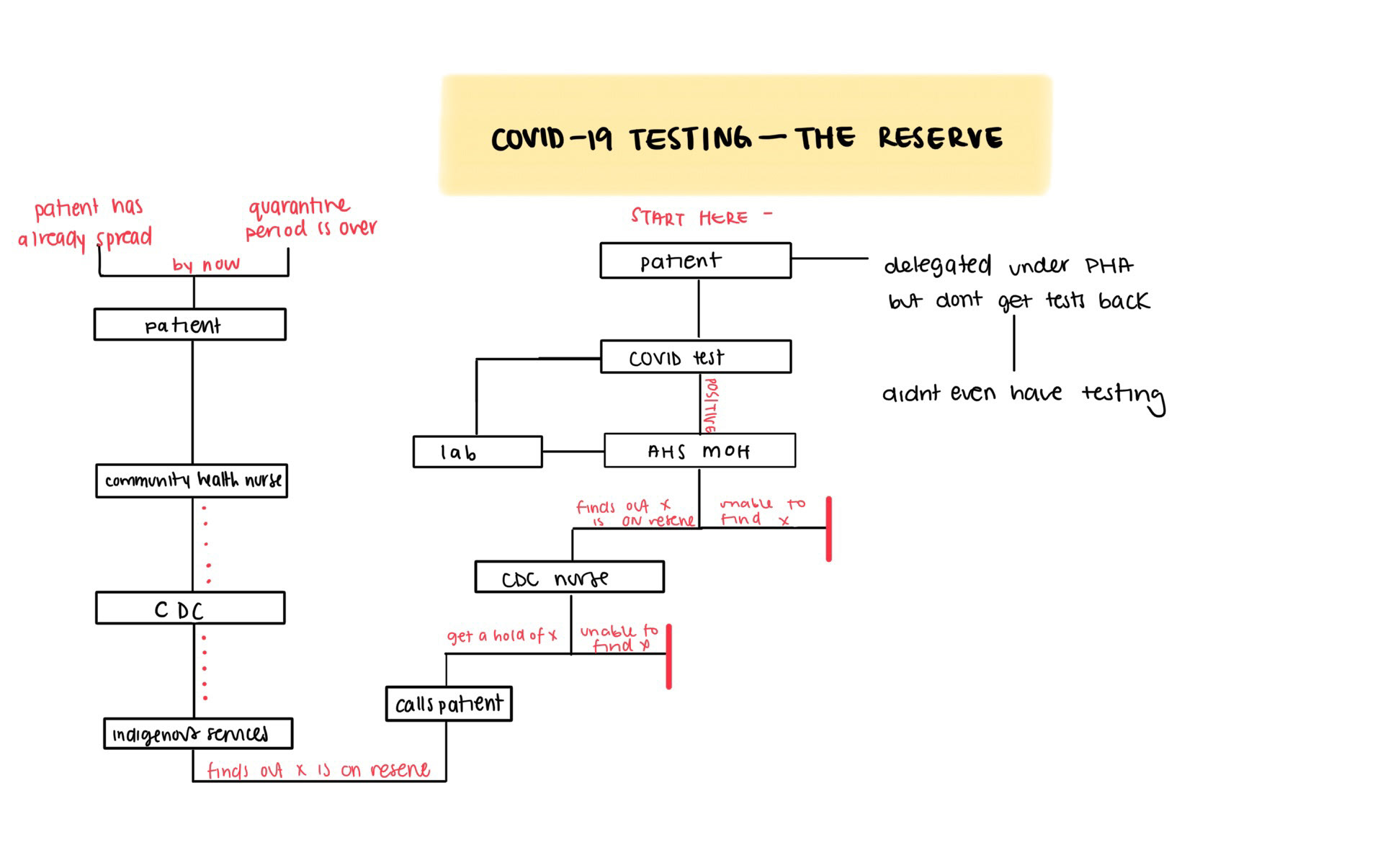

An unfortunate commonality surfaced—the history of communicable diseases instilling fear and apprehension among Indigenous peoples. This revelation not only reshaped our understanding of the pandemic response the community was taking, but also reshaped how we approached our research as well. Thus, the standard public health approach (as employed in the City) towards the pandemic could not be taken. Rather, there was need for a holistic approach—rooted in compassion, empathy, and protection. This approach aimed not only at combatting the immediate issue but also to heal the ingrained fear of the system itself. In this journey, the stories of resilience, adaptation, and community strength unfolded, guiding our understanding of healthcare in the context of Indigenous communities during the challenging times of the pandemic.

A Visual Snapshot of Time

The final deliverable, a system map, delved into a brief timeframe where COVID-19 and Indigenous communities. It sources data from community provider interviews and the comprehensive pandemic response. Five distinct categories, organizing the map's nodes emerged through our research: social, economic, environment, political (decisions made by governmental bodies), and health. This categorization allows users to delve into each area independently, unveiling the intricacies of the pandemic response. The size of each category corresponds directly to the generated and gathered data. The social and health categories played a pivotal role in Indigenous communities' pandemic response. Lines connecting nodes reveal the barriers and access points, symbolized by solid and dashed lines, respectively. No arrowheads signify the non-linear, non-hierarchical nature of these connections. Some nodes repeat in each category, showcasing recurring patterns.

Choose your exploration path with an interactive version of the system map—allowing you to isolate different elements and layers of data. This design decision ensures readability and emphasizes dominant connections within the map.

This visual journey is a tribute to the tireless efforts of providers during the pandemic, acknowledging their selfless work. Through this research, the remarkable resilience and strength of Indigenous communities can be witnessed. May this serve as a reminder in acknowledging our privilege and empathizing with the vulnerabilities facing marginalized communities around us.